When a friend recommends a novel, my first question is never, “What's it about?” Instead, I always ask who wrote it. If not familiar with the author, and if I know my friend has discriminating tastes, I ask, “What's the writing like?” I once loaned my copy of Tolkien's The Children of Húrin to a friend with the qualifier, “The subject matter is pretty morbid.” This triggered a raised brow. “But,” I said, “the writing is superb.” To which he replied, “Well, it's Tolkien!”

Whether you revel in stories involving space aliens, 19th century sleuths, druids of antiquity, lovers in the Victorian Era, modern day cyber criminals, fairies with an inexhaustible supply of pixie dust, or talking animals, no qualifier exists to gauge the value or validity of such interests. To each his (or her) own, I say.

The rules of grammar, on the other hand, while not the ultimate factor for determining a thumbs up or down of any given work, is a good first step toward gauging quality of prose and clarity of thought. In fact, the whole point of these rules, though admittedly malleable, is to encourage comprehension. When it comes to novels, this criterion is one of many among a host of objective standards for evaluating, dare I say, the discipline known as fine writing.

Because suspension of disbelief is individual and each reader's threshold is different, my focus isn't so much about what happens in a story but rather how it's conveyed. As a great writer and friend has said, “It's not about what you write, but how you say it. If you get the words right, it's like music on a page.”

So to be clear, this critique is concerned with the writer's execution, delivery, style, and command of the language, not subject matter. This is my only stipulation. Well, that and an engaging story. I don't think that's too much to ask.

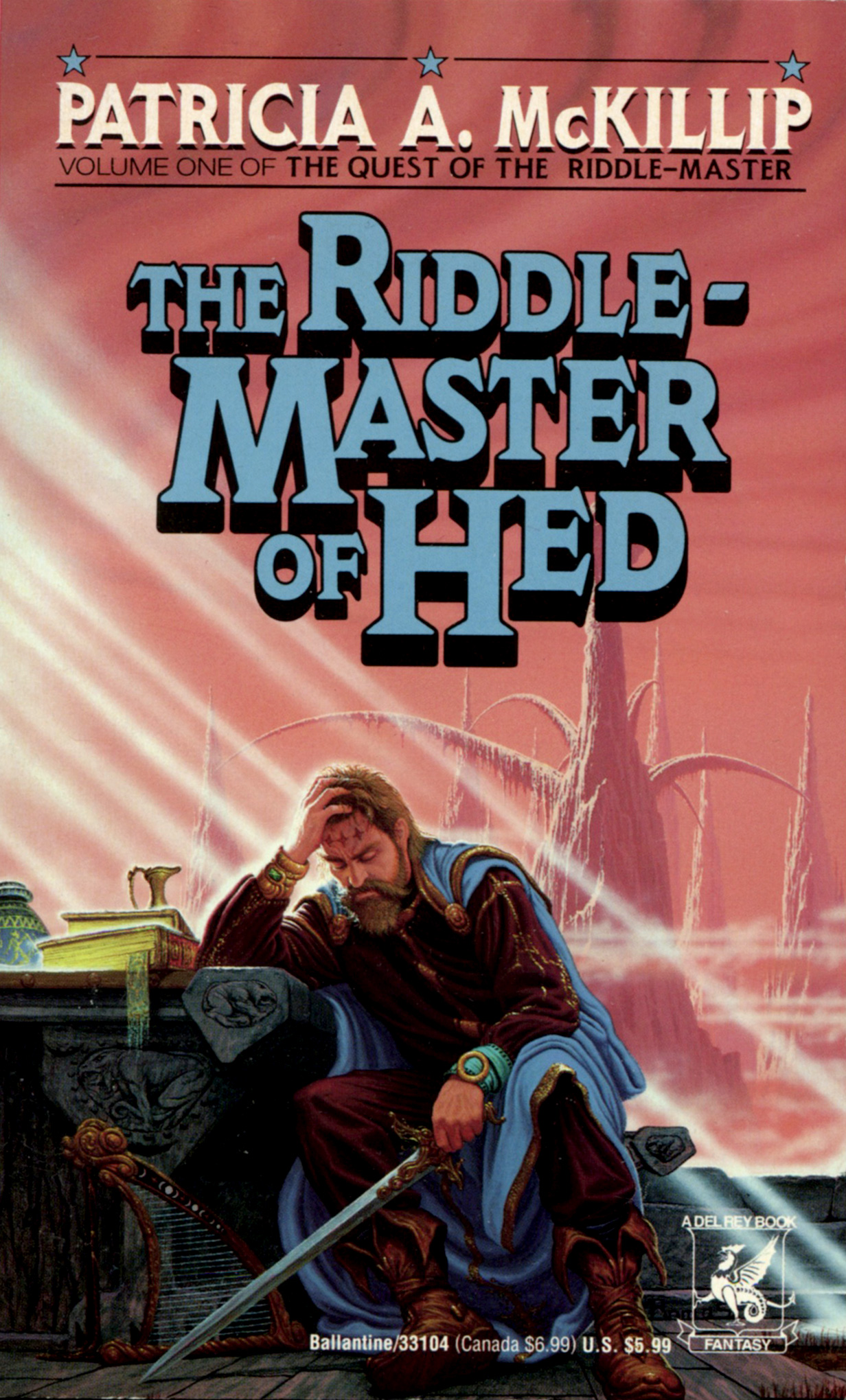

This is why, despite my aversion to much of the perversity and despairing content in any number of Nabokov's novels, I tend to give his stuff five out of five stars. For the same reason, regardless my love for fantasy fiction, I'm giving The Riddle-Master of Hed a negative nine. Essentially, this is because Nabokov is a master wordsmith, whereas McKillip can't compose a coherent sentence.

Whether you revel in stories involving space aliens, 19th century sleuths, druids of antiquity, lovers in the Victorian Era, modern day cyber criminals, fairies with an inexhaustible supply of pixie dust, or talking animals, no qualifier exists to gauge the value or validity of such interests. To each his (or her) own, I say.

The rules of grammar, on the other hand, while not the ultimate factor for determining a thumbs up or down of any given work, is a good first step toward gauging quality of prose and clarity of thought. In fact, the whole point of these rules, though admittedly malleable, is to encourage comprehension. When it comes to novels, this criterion is one of many among a host of objective standards for evaluating, dare I say, the discipline known as fine writing.

Because suspension of disbelief is individual and each reader's threshold is different, my focus isn't so much about what happens in a story but rather how it's conveyed. As a great writer and friend has said, “It's not about what you write, but how you say it. If you get the words right, it's like music on a page.”

So to be clear, this critique is concerned with the writer's execution, delivery, style, and command of the language, not subject matter. This is my only stipulation. Well, that and an engaging story. I don't think that's too much to ask.

This is why, despite my aversion to much of the perversity and despairing content in any number of Nabokov's novels, I tend to give his stuff five out of five stars. For the same reason, regardless my love for fantasy fiction, I'm giving The Riddle-Master of Hed a negative nine. Essentially, this is because Nabokov is a master wordsmith, whereas McKillip can't compose a coherent sentence.

As I mentioned in a previous post, I recently came across an online

list from BuzzFeed: “The 51 Best Fantasy Series Ever Written.” So, after a long hiatus, I decided to return to the genre in the hopes of reading some of the

more, presumably, better novels of that genre.

So far, I'm regretting that decision. In fact, if I've learned anything from this most recent novel, apart from what not to do as a writer, it's that Del Ray has some fairly low standards. Based on this entry and a few others on the list I've read, most modern writers of this genre, subject matter aside, are at best subpar and at worst in need of a composition 101 refresher course.

First, the title of this novel is beyond misleading; it's false

advertising. The protagonist Morgon is hailed as a riddle-master. Morgon is

said to have battled another riddle-master and won a king's crown

before the story begins. (We readers are deprived of this scene.) Yet

despite the “riddles” presented to Morgon throughout the novel,

as well as the “riddles” referred to in his game of wits with the

other riddle-master off-stage, none of these “riddles” are actual

riddles.

Indeed, someone needs to explain to the author that while a riddle is a sort of question, a question is not a riddle. Like other word problems, riddles frequently contain clues; questions generally don't. Granted, some riddles offer no clues but rather require one's powers of deduction, and some riddles are deliberately misleading. Still, there's a considerable difference between “What three letters transform a boy into a man?” (Age) and “What's the capital of Kansas?” (Topeka). Here are some other legitimate riddles: “How many months contain 28 days?” (All 12 of them.) “A woman has seven children. Half of them are boys. How is this possible?” (They're all boys.) “I have a head. I have a tail. But I have no body. What am I?” (A coin.) Or, to be precise, a talking coin.

In this novel, not a single clever query or rhyme is offered. Instead, we get questions like, “Who is the man in the red robe?” Neither the protagonist nor the reader knows. We've never seen such a man, and when the question is asked, no man is about, red-robed or otherwise.

Leaving aside the plot, let's further ignore the fact that the

protagonist in this novel has three inexplicable stars on his

forehead. (I say inexplicable because the author never explains these

markings in the story.) Nor

will we examine the alleged appeal of a protagonist taught to become

a shape shifter, a vesta, whatever that is (the author doesn't

specify, nor is a vesta listed in the glossary at the back of the

book, though from what I gather it's a kind of elk or deer). Nor the

fact that another character teaches the protagonist how to

temporarily become a tree. Whether these sorts of things appeal to

readers I leave to the readers since, as I say, personal taste, and hence subject matter, is subjective.

Having said that, this is by far the worst novel

I've ever read. I offer some examples. Keep in mind McKillip, the

author, has an MA in English, and this novel ranked 13th in a 1987 reader's poll for All-Time Best Fantasy Novels and 22nd in their 1998 poll. Nevertheless McKillip tends to compose the most clumsy sentences this side of the Mississippi. Not a single paragraph shines, and some of her awkward construction is downright horrid.

Heureu had risen. He gripped Morgon firmly; his voice sounded distant, then returned, full. “I should have thought …”

His

voice returned full? From what? From its distance? Does it matter whether Heureu's voice is full or sounds distant or

returns?

The harpist rose. His face was hollowed, faintly lined with weariness; his voice, calm as always, held no trace of it. “How do you feel?”

Held

no trace of what? Of weariness? Why write this way? How about this:

The harpist rose. He looked weary. Calmly, he asked, “How do you

feel?”

He smiled reminiscently.

How exactly does one smile “reminiscently”?

Morgon drew a breath. His head bowed suddenly, his face hidden from the harpist. He was silent for a long time while Deth waited, stirring the fire now and then, the sparks shooting upwards like stars. He lifted his head finally.

Point of view violations aside, the author writes reams of confusing narrative like this. Characters constantly look one another in the eye, look away, look down, turn, lift or lower their heads, etc. Meanwhile, antecedents get shuffled and the reader is left to guess about who's speaking and doing what. I'm still not clear which one of them, Deth or Morgon, was stirring the fire "now and then" nor who to ascribe the pronoun to in the last sentence. And since when do sparks from a fire remind one of stars?

Morgon drew an outraged breath.

What precisely is an outraged breath? Morgon was outraged? Got it. He sighed in exasperation? Maybe. How about telling us simply, “Morgon was outraged” or “Morgon was exasperated”?

The next morning, he saw Herun, a small land ringed with mountains, fill like a bowl with dawn.

Do bowls ordinarily fill with dawn? Essentially this allusion is aided by the appearance of mountains which “ringed” the “small land”. Fair enough. But the phrase “a small land ringed with mountains” is problematic, given Morgon's decision beforehand to avoid crossing or traveling through mountains of any kind. In other words, how did Morgon reach a small land ringed with mountains without first traveling through said mountains which the author told us earlier he'd already decided to avoid?

He closed his eyes, smelled, unexpectedly, the autumn rains falling over three-quarters of Hed.

Hed is a region. How does the protagonist know the extent of its rainfall? Imagine standing on a stretch of farm land while it's raining. Could you determine whether only half the farm was receiving rain? Or two-thirds? Or “three-quarters”? Plus, even if Morgon possessed some inexplicable preternatural sight for perceiving rainfall ratio to acreage, we're told at the beginning of the sentence that he closed his eyes.

I

leave it to the reader to consider the structure of the following

sentences, their relevance, and the quality of the similes:

Gently as small birds landing on his mind came questions he no longer had to answer.

The fire sank low, like a beast curling to sleep.

Morgon, his eyes on the fire, felt his mind fill with faces …

He was almost unable to breathe.

He stirred, his face turning to Har's. Their eyes met [for] a moment in an unspoken knowledge of one another.

He paused, looking again at Har; his hands moved a little, helplessly, as though groping for a word.

I'm reminded of Jean Eggenschwiler's observation in his fantastic book Writing: Grammar, Usage, and Style, “Most can distinguish between solid content and inflated trivia.”

Danan drew a breath to speak, but said nothing.

He leaned forward, his face etched with fire, and roused the half-log on the hearth. A flurry of sparks burned in the air like fiery snow.

So flames from the hearth don't illuminate his face; they etch it with fire? And what is a half-log anyway? Isn't this comparable to half a hole? Isn't a hole, regardless its size, still a hole? And since when do sparks from a fire burn like snow, fiery or otherwise?

… the wizards themselves, skilled, restless and arbitrary, would never had [sic] dreamed of trying to kill a land-ruler.

If the wizards are “arbitrary,” what's to prevent them from dreaming such a thing, or anything for that matter?

Morgon felt eyes on his face.

I assume this is comparable to feeling that you're being watched, but not only is this a poor choice of words, it's an utterly frivolous point to make, considering the fact that Morgon is eating in a public place. It stands to reason diners would steal occasional glances at fellow diners.