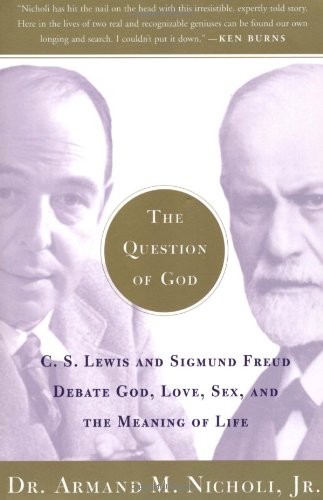

The

Prologue opens with their funerals – a couple of quotes from

attendees, snippets and summaries from their obituaries, and a brief

montage of their accomplishments. A tasty appetizer to prime the

palate for the entrée to come.

The

lives of these two intellectual icons

overlapped in both space and time: Freud lived “not far from

Oxford” where, and while, Lewis was a young professor, and the two

were separated only by a generation; Lewis' body was buried just 24

years after Freud's was cremated. Both wrote passionately and

extensively about their philosophies, and the two shared an interest

in literature and psychoanalysis. They published several books,

including autobiographies.

Nicholi

sets out to address two fundamental questions “What should we

believe?” and “How should we live?” He examines Freud's and

Lewis' childhoods, their relationships with their families, the

historical events that impacted their personal and professional

lives, and the philosophies they espoused based

not only on their published works but on the less public thoughts

contained in the journals they kept and the hundreds of letters they

wrote to friends and family. More (maybe most) importantly,

the writer explores whether these men practiced what they preached,

and, subsequently, whether their lives were enriched.

Both

Freud and Lewis experienced heart wrenching tragedies and deep

sorrows. Nicholi draws from their letters to expose these wounds.

Their deaths near the close of the work, though anticipated, came too

soon and made me scrunch my face and clumsily wipe my cheeks.

Detractors

have expressed displeasure with Nicholi's conclusions. Some insist

the pairing of the two men is unfair to Freud, that Nicholi stacks

the deck against atheism, that instead Lewis should've been pitted

against the likes of Sam Harris or Carl Sagan.

These

objections ignore several factors, some I've already mentioned. Maybe

most relevant is what Nicholi says in the Prologue:

Wherever Freud raises an argument, Lewis attempts to answer it.

Thirty years before the publication of this book in 2003, Harvard invited Nicholi to teach a

course on Freud. He has been teaching the undergraduates there ever since, as well as the Harvard Medical School students for at least a decade. Initially, the

course consisted exclusively of Freud's philosophical views, but as

Nicholi writes:

Roughly half my students agreed with him, the other half strongly disagreed. When the course evolved into a comparison of Freud and Lewis, it became much more engaging, and the discussions ignited.

We

should also remember that Freud gave us “terms such as ego,

repression, complex, projection, inhibition,

neurosis, psychosis, resistance, sibling

rivalry, and Freudian slip.” Lewis was

“perhaps the 20th century's most popular proponent of

faith based on reason” and inspired a “vast number of ...

societies in colleges and universities”.

During World War II his Broadcast talks made his voice second only to Churchill's as the most recognized on the BBC.

It's

difficult to downplay “the sheer quantity of personal,

biographical, and literary books and articles on Lewis” published

since his passing.

Despite

Sagan's highly entertaining Cosmos series, his important work

in astronomy and astrophysics, as well as his compelling commentary

as it pertains to cosmology, his influence doesn't compare. As for

Harris' haphazard reasoning and saccharin science, anyone who believes

this atheist would stand a chance against the likes of Lewis is

engaged in wishful thinking. A brief sampling of online video or audio debates

between Harris and a number of theist philosophers and scientists

confirms this. Critical thinking is not his forte.

I

can't imagine a skeptic coming away from this work still convinced

atheism has anything attractive to offer. Freud's philosophy led to

fits of depression and repeated thoughts of suicide; Lewis' faith

resulted in personal fulfillment so that even at his most desperate

and lonesome hour, he discovered not only an alternative to despair

but a joy that surpassed his expectation.

A

compelling account of two legends, their legacies, and the

implication and consequence of their philosophies. Well written and

researched (40 pages of notes and bibliography).

No comments:

Post a Comment